GIMP

News

Docs

Tutorials

More

Luminosity masks are basically layer masks that are built around specific tones in an image. They are derived from the image data itself, and focused on a specific range of tonal values. The benefit of using these types of masks is that when targeting tonal ranges the mask itself is self-feathering, helping to avoid problems with blending and hard transitions.

Being able to selectively modify an image based on particular tonal regions can be a very powerful method of editing. Need to brighten up the mid-tones in an image without effecting shadows or highlights? Want to split-tone an image with different colors? Need to increase contrast only in the darkest shadows? All of these are trivially easy once you begin considering your image as a collection of tonal ranges.

This tutorial will assume you are already familiar with layer masks. If not (or you just want to brush up), I recommend you read through the Layer Masks tutorial first.

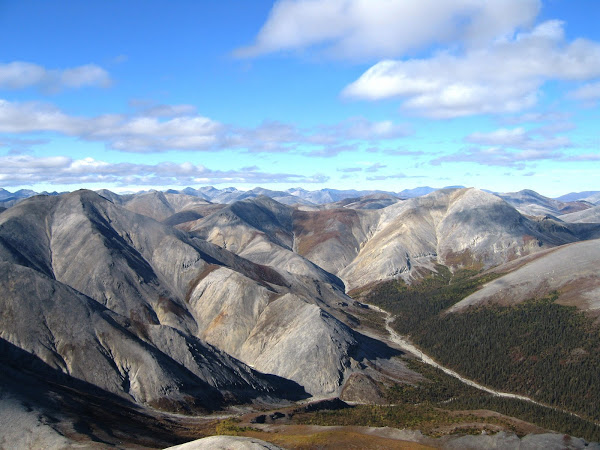

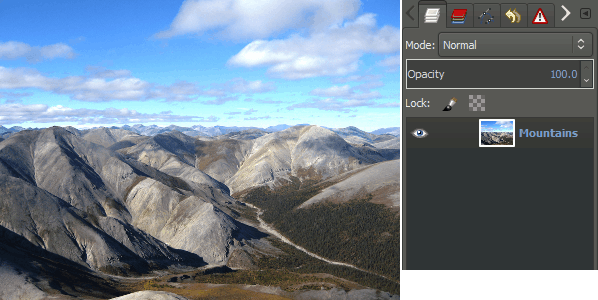

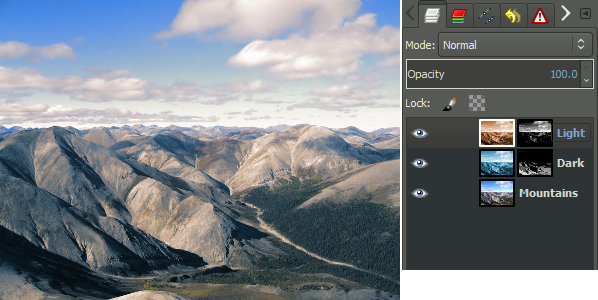

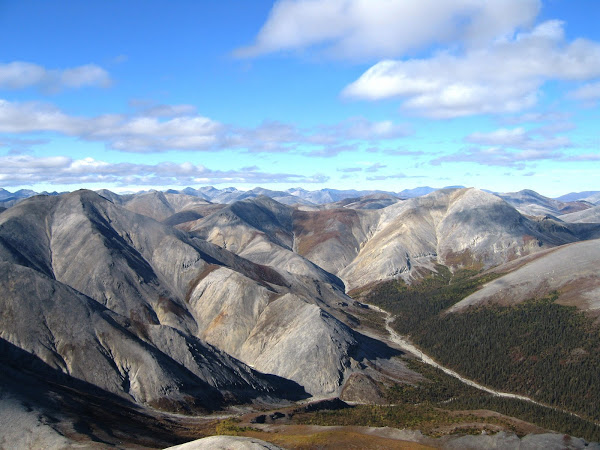

For this tutorial I’ll be using this image by the West Arctic National Parklands:

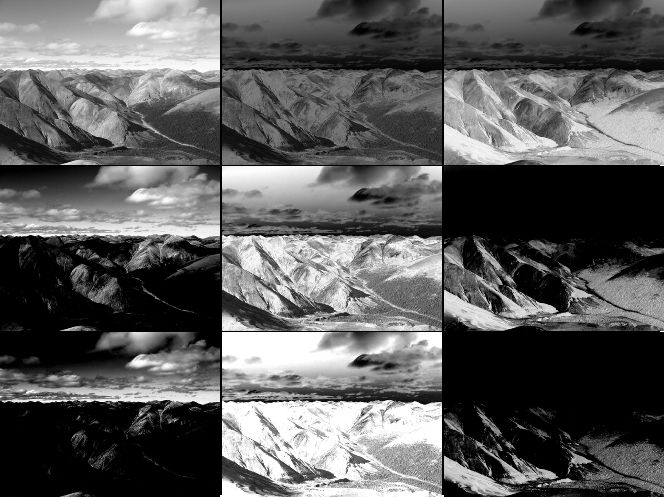

After going through this tutorial, we will generate channels in GIMP corresponding to these six different luminosity regions in the image:

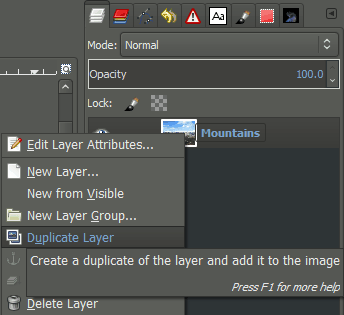

To begin creating the masks we will need to first get a luminosity representation of the image. This is easily achieved by duplicating the base layer, and desaturating it using Luminosity as the conversion option.

Either through the menus, or by Right-Clicking on the base layer in the Layer Dialog:

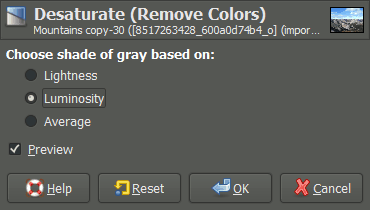

Now desaturate the duplicated layer using Luminosity as the method:

This desaturated copy of your color image represents the “Lights” channel. Now we want to create a new channel based on this layer.

The easiest way to do this is through the Channels Dialog. If you don’t see it, you can open it by going to:

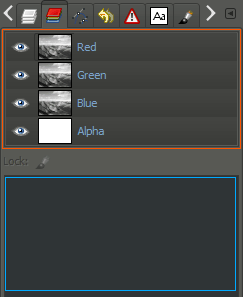

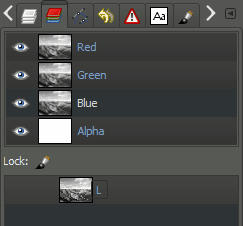

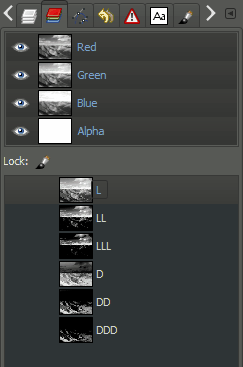

On the top half of this window you’ll see the an entry for each channel in your image (Red, Green, Blue, and Alpha). On the bottom will be a list of any channels you have previously defined.

To create a new channel that will become your “Lights” channel, drag any one of the RGB channels down to the lower window (it doesn’t matter which - they all have the same data due to the desaturation operation).

Now rename this channel to something meaningful (like “L” for instance!), by double-clicking on its name (in my case it‘s called “Blue Channel Copy”) and entering a new one.

This now gives us our “Lights” channel, L :

With the “Lights” channel created, we can use it to create the inverse, the “Darks” channel.

To create the “Darks” channel, it helps to realize that it should simply be the inverse of the “Lights” channel. We can get this selection through a few simple operations.

We are going to basically select the entire image, then subtract the “Lights” channel from it. What is left should be our new “Darks” channel.

First, select the entire image:

Remember that you should be seeing the “marching ants” around your selection - in this case the entire image.

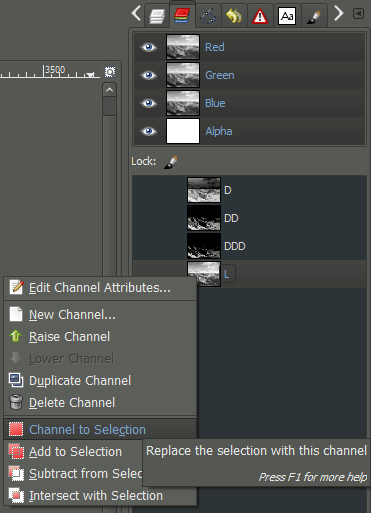

With the entire image selected, we just have to subtract the “Lights” channel. In the Channels dialog, just Right-Click on the “Lights” channel, and choose “Subtract from Selection”:

You’ll now see a new selection on your image. This selection represents the inverse of the “Lights” channel…

Now we just need to save the current selection to a new channel (which we’ll call… Darks!). To save the current selection to a channel, we can just use:

This will create a new channel in the Channel dialog (probably named “Selection Mask copy”). To give it a better name, just Double-Click on the name to rename it. Let’s choose something exciting, like “D”!

At this point, you’ll have a “Lights” and a “Darks” channel. If you wanted to create some channels that target darker and darker regions of the image, you can subtract the “Lights” channel again (this time from the current selection, “Darks”, as opposed to the entire image).

Once you’ve subtracted the “Lights” channel again, don’t forget to save the selection to a new channel (and name it appropriately - I like to name subsequent masks things like “DD” in this case - if I subtracted again, I’d call the next one “DDD” and so on…).

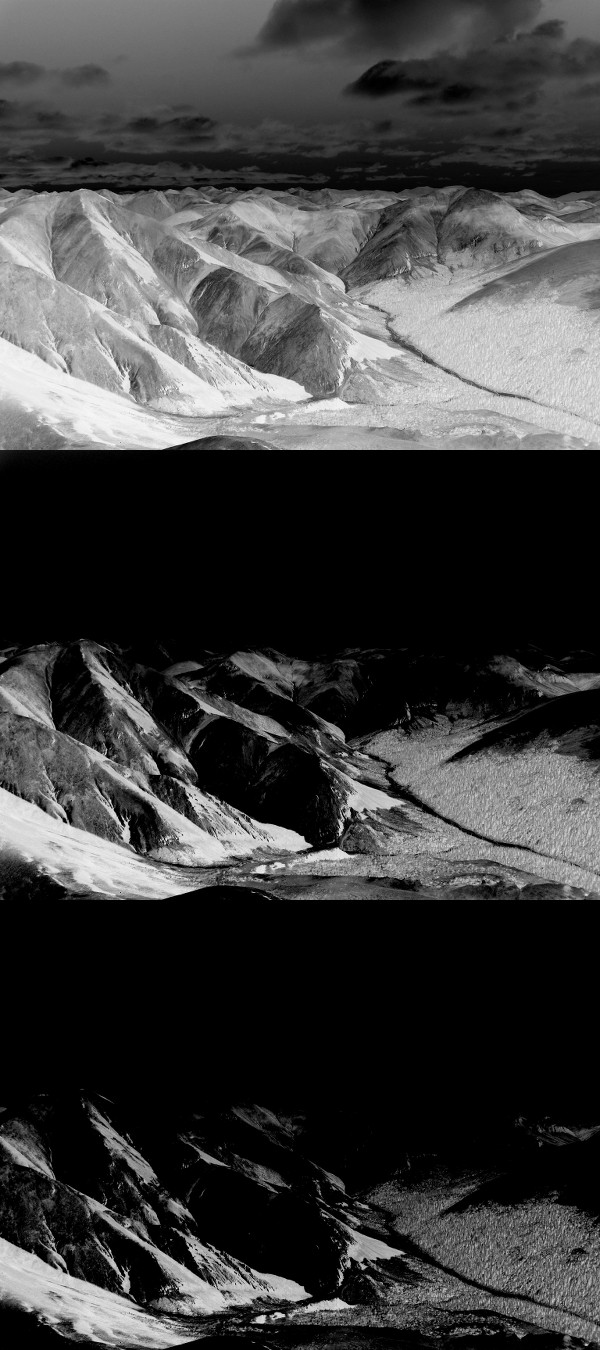

I’ll usually make 3 levels of “Darks” channels: D, DD, and DDD:

Here is what the three different channels of Darks look like:

At this point we have one “Lights” channel, and three “Darks” channels. Now we can go ahead and create two more “Lights” channels, to target lighter and lighter tones.

The process is identical to creating the darker channels, just in reverse.

To get started, activate the “Lights” channel as a selection (Right-Click on the “Lights” Channel):

With the “Lights” channel as a selection, now all we have to do is Subtract the “Darks” channel from it. Then save that selection as a new channel (which will become our “LL” channel, and so on…):

To get an even lighter channel, you can subtract D one more time from the selection so far as well.

Here are what the three channels look like, starting with L up to LLL:

By this point, we’ve got 6 new channels, three each for light and dark tones:

Now we can generate our mid-tone channels from these.

The concept of generating the mid-tones is relatively simple - we’re just going to intersect dark and light channels to produce whats left - midtones.

To get started, first select the “L” channel, and set it to the current selection (just like above). Right-Click → Channel to Selection.

Then, Right-Click on the “D” channel, and choose “Intersect with Selection”.

You likely won’t see any selection active on your image, but it’s there, I promise. Now as before, just save the selection to a channel:

Give it a neat name. Sayyy, “M”? :)

You can repeat for each of the other levels, creating an MM and MMM if you’d like (using LL/DD and LLL/DDD respectively).

Now remember, the mid-tones channels are intended to isolate mid values as a mask, so they can look a little strange at first glance. Here’s what the basic mid-tones mask looks like:

Remember, black tones in this mask represent full transparency to the layer below, while white represents full opacity, from the associated layer.

The basic idea behind creating these channels is that you can now mask particular tonal ranges in your images, and the mask will be self-feathering (due to how we created them). So we can now isolate specific tones in the image for manipulation.

Previously, I had shown how this could be used to do some simple split-toning of an image. In that case I worked on a B&W image, and tinted it. Here I’ll do the same with our image we’ve been working on so far…

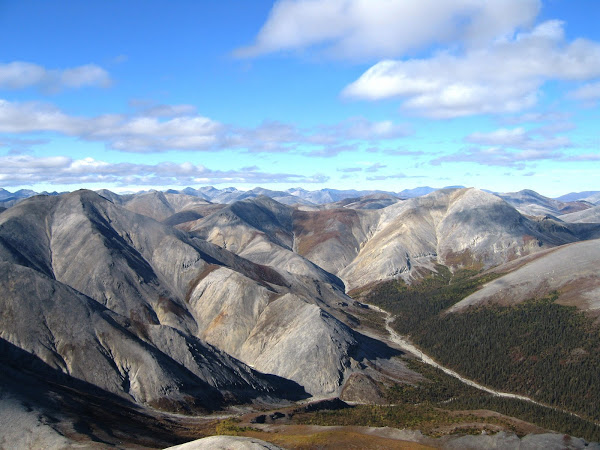

Using the image I’ve been working through so far, we have the base layer to start with:

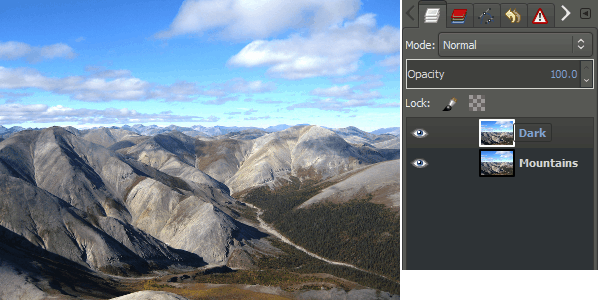

We are going to want two duplicates of this base layer. One to tone the lighter values, and another to tone the darker ones. We’ll start by considering the dark tones first. Duplicate the base layer:

Then rename the copy something descriptive. In my example, I’ll call this layer “Dark” (original, I know):

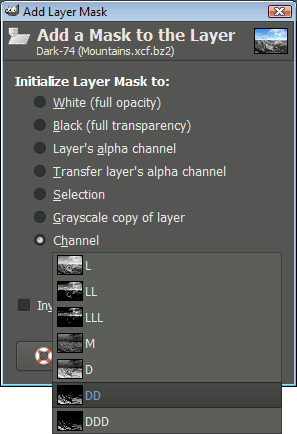

Now we can add a layer mask to this layer. You can either Right-Click the layer, and choose “Add Layer Mask”, or you can go through the menus:

You’ll then be presented with options about how to initialize the mask. You’ll want to Initialize Layer Mask to: “Channel”, then choose one of your luminosity masks from the drop-down. In my case, I’ll use the DD mask we previously made:

Now you’ll have a Dark layer with a DD mask that will restrict any modification you do to this layer to only apply to the darker tones.

Make sure you select the layer, and not it’s mask, by clicking on it (you’ll see a white outline around the active layer). Otherwise any operations you do may accidentally get applied to the mask, and not the layer.

At this point, we now want to modify the colors of this layer in some way. There are literally endless ways to approach this, bounded only by your creativity and imagination. For this example, we are going to tone the image with a cool teal/blue color (just like before), which combined with the DD layer mask, will restrict it to modifying only the darker tones.

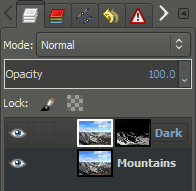

So I’ll use the Colorize option to tone the entire layer a new color:

To get a Teal-ish color, I’ll pull the Hue slider over to about 200:

Now, pay attention to what’s happening on your image canvas at this point. Drag the Hue slider around and see how it changes the colors in your image. Especially note that the color shifts will be restricted to the darker tones thanks to the DD mask being used!

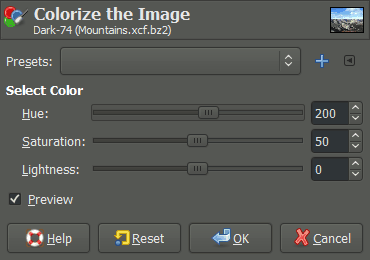

To illustrate, here are four images where the Hue has been changed in each one. Notice how the color shifts are constrained to darker tones due to the DD mask being active:

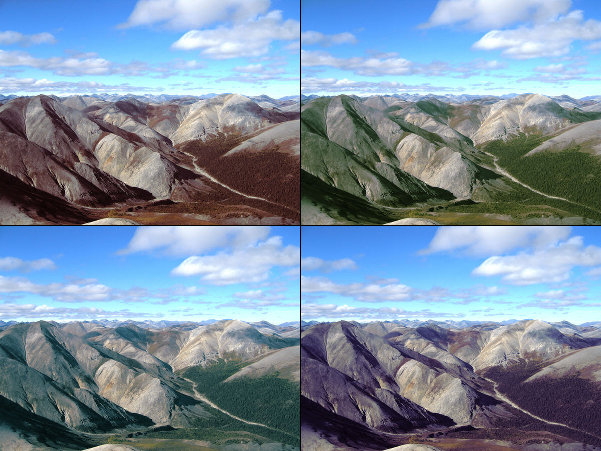

So after I choose a new Hue of 200 for my layer, I should be seeing this:

Now just repeat the above steps, but this time for the light tones. So duplicate the base layer again, and add a layer mask, but this time try using the LL channel as a mask.

For the lighter tones, I chose a Hue of around 25 instead (more orange-ish than blue):

In the end, here are the results that I achieved:

Compared to the original we started with:

The real power here comes from experimentation. I encourage you to try using a different mask to restrict the changes to different areas (try the LLL for instance). You can also adjust the opacity of the layers now to modify how strongly the color tones will effect those areas as well. Play!

The mid-tone masks were very interesting to me. In Tony’s original article, he mentioned how much he loved using them to provide a nice boost to contrast and saturation in the image. Well, he’s right. It certainly does do that! (He also feels that it’s similar to shooting the image on Velvia).

Let’s have a look.

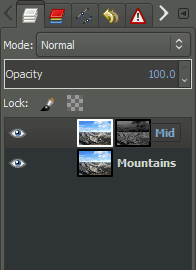

I’ve deleted the layers from my split-toning exercise above, and am back to just the base image layer again.

To try out the mid-tones mask, we only need to duplicate the base layer, and apply a layer mask to it.

This time I’ll choose the basic mid-tones mask M.

What’s interesting about using this mask is that you can use pretty aggressive curve modifications to it, and still keep the image from blowing up. We are only targeting the mid-tones.

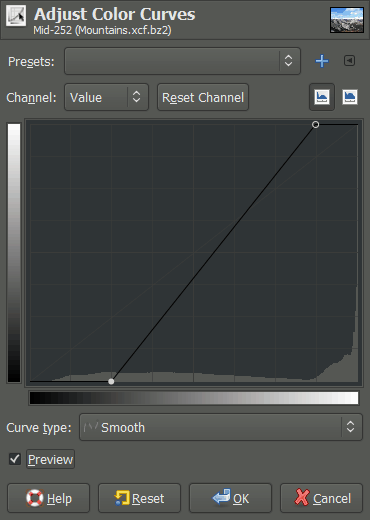

To illustrate, I’m going to apply a fairly aggressive compression to the curves by using Adjust Color Curves:

When I say aggressive, here is what I’m referring to:

Here is the effect it has on the image when using the M mid-tones mask:

Compared to the original we started with:

As you can see, there is an increase in contrast across the image, as well a nice little boost to saturation. You don’t need to worry about blowing out highlights or losing shadow detail, because the mask will not allow you to modify those values.

This is just another tool in our mental toolbox of image manipulation, but it’s a very powerful tool indeed. When considering your images, you can now look at them as a function of luminosity - with a neat and powerful way to isolate and target specific tones for modification.

As always, I encourage you to experiment and play!

The original tutorial this was adapted from may be found here (possibly with updated information).

GIMP Tutorial - Luminosity Masks (text) by Pat David.

GIMP Tutorial - Luminosity Masks (text) by Pat David.

Licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License.